Mental Illness Awareness Week is October 3rd to 9th, 2021, and October 7th is National Depression Screening Day. To learn more about Mental Illness Awareness Week and the campaign from the National Alliance on Mental Health (NAMI) here.

- The latest data from Kantar Health’s National Health and Wellness Survey found that approximately 1 in 6 people have symptoms of depression but don’t recognize it.

- The data shows that untreated depression adds $8,840 to healthcare utilization costs, per year, when compared to those who get diagnosed for depression and receive treatment.

Just “Everyday Life Problems”

As Director of Research Strategy at Twill, with a PhD in Psychology and over a decade of research related to depressive symptoms, I have a professional perspective on depression. More recently, however, I’ve also been on a very personal journey with the disease.

Three years ago, I found myself struggling to get out of bed. I wasn’t eating; I had to force myself to eat a small energy bar once a day just to make sure I didn’t starve myself. I couldn’t bring myself to check my work email for days.

It was all I could do to get up in the morning, make sure my kids were ready for school, pack their lunches, drop them off and return home to crawl back into bed and watch the latest series on Netflix until it was time to pick them up.

I’m trained in psychology and in how to conduct research that focuses on mental health, so I knew my behavior wasn’t “normal.” And yet, in spite of all of my experience and insight, when friends asked me if I considered speaking to a therapist or getting on antidepressants, my answer was always “no, it’s just situational depression - I just need things to get better”.

My father had been diagnosed with terminal cancer, I was exhausted from single parenthood, I was burnt out at work, and I had just ended a complicated relationship. I used all of these things to rationalize my depressive symptoms and avoid seeking help.

I never did seek out a diagnosis, or treatment. In hindsight, I suffered for the better part of a year because I decided it was easier to avoid what felt like the additional burden of seeking out help.

Unfortunately, this kind of rationalization is not uncommon among people struggling with depressive symptoms.

One qualitative study of adults with personal or vicarious experiences with depression found that many of the study’s participants who were aware of their symptoms delayed treatment-seeking by rationalizing their symptoms as typical “everyday life problems” [1].

The same study showed that many participants even reported being unaware there was a problem, sometimes for years, even if they had had prior treatment for depression [1].

Depression Goes Unrecognized Regularly

The data shows that my story is quite common. In 2018, 7.2% of adults in the United States had at least one episode of major depression [2], and only about one-in-four likely received treatment [3].

However, if we account for undiagnosed cases of major depression, that number could double [4], and even more people may experience mild to moderate levels of depressive symptoms.

For example, the aforementioned research conducted by Twill’s Health Economics and Outcomes Research team using Kantar’s National Health and Wellness data showed that 17.07% of survey respondents said “no” when asked if they experienced depressive symptoms, but had at least mild depression on the PHQ-9, a validated measure of depression.

All in, that’s about 1 in 6 people who had not only undiagnosed depression, but unrecognized depression. And while many had mild to moderate levels of depression, 28% of the people with unrecognized depression had PHQ-9 scores showing moderately-severe to severe levels of depression (PHQ-9 scores of 15 or higher).

Undiagnosed depression may be even more common among people living with chronic physical conditions. In one analysis of data from the World Health Organization, drawn from people who had been diagnosed with a variety of chronic conditions like diabetes, arthritis, and chronic lung disease across six different countries, found that 87% of identified cases of depression in this sample were undiagnosed [5].

Depression May Not Look like "Depression"

One reason why people might struggle to identify what they’re feeling as depression is that our depressive symptoms may not always look or feel the way we have seen it depicted in the media - or even by how it is measured on many surveys designed to assess depressive symptoms for that matter.

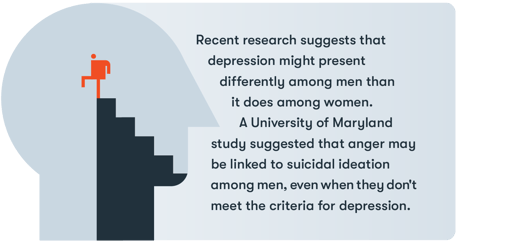

Recent research suggests that depression might present differently among men than it does among women.

Recent research suggests that depression might present differently among men than it does among women.

A study conducted by researchers at the University of Maryland and University of Utah suggested that anger may be linked to suicidal ideation among men, even when they don’t meet criteria for depression, leading the researchers to think that anger may be one way men externalize depression [6].

Other researchers have argued that depression in men can be associated with other types of externalizing behaviors, like sensation-seeking and substance abuse [7]. Consistent with this argument, one meta-analysis found that substance use, risk taking, and poor impulse control are more common among men with depression than among women with depression [8]. Women with depression, on the other hand, are more likely to report depressed mood, weight changes, and appetite or sleep disturbances [8].

This is why some researchers have argued that depression screening, particularly among young men, should include assessing externalizing symptoms of depression too [9], and specific measures for assessing depression in men have been developed [7, 10].

Another hurdle to accurately identifying depression is due to the fact that much of what we know about depression comes from research and theories developed in the Western World. It’s not until the past few decades that psychology has started to recognize that many of the beliefs we hold about psychology may not apply to other parts of the world.

For instance, some researchers argue that Eastern cultures experience more of the somatic - or physical - symptoms of depression than in Western cultures. Indeed, research has shown that Chinese participants who strongly identified with Asian culture were more likely to report somatic symptoms of depression than Australians, or Chinese participants who identified less with cultural norms [11].

Other research has shown that Vietnamese participants reported more somatic symptoms than German participants, like headaches, chest pain, or dizziness [12].

People who experience more of these physical symptoms of depression may be less likely to recognize their condition as depression and more likely to visit their primary care physician complaining about physical symptoms, leading to lower rates of diagnosis and treatment for depression among somatizers compared to psychologizers [13].

The Burden of Undiagnosed Depression

The average length of time between the onset of depression and receiving treatment is estimated to be 8 years [14]. In that time, people with undiagnosed and untreated depression pose a greater economic burden in terms of direct and indirect costs.

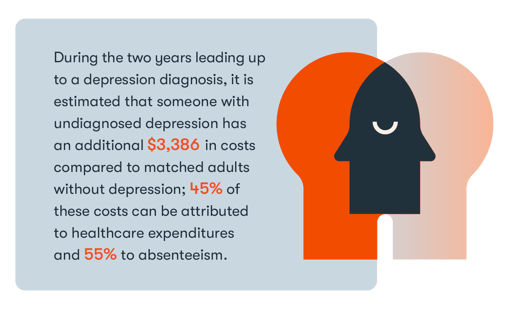

For example, during the two years leading up to a depression diagnosis, it is estimated that someone with undiagnosed depression has an additional $3,386 in costs compared to matched adults without depression; 45% of these costs can be attributed to healthcare expenditures and 55% to absenteeism [14].

For example, during the two years leading up to a depression diagnosis, it is estimated that someone with undiagnosed depression has an additional $3,386 in costs compared to matched adults without depression; 45% of these costs can be attributed to healthcare expenditures and 55% to absenteeism [14].

What’s more, excess costs increase over time, closer to the time of diagnosis, suggesting that diagnoses may occur because symptoms have become more severe and debilitating [14].

In our analysis of the Kantar National Health and Wellness Survey data, we found that the average incremental unadjusted costs for someone with unrecognized depression were $8,840 higher per year compared to costs associated with individuals with diagnosed and treated depression.

Digital Health Platforms Broaden Opportunities for Screening

In 2016, the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force updated its recommendations for depression screenings within medical care to recommend screening all adults, including pregnant and postpartum women, as part of routine medical care [15].

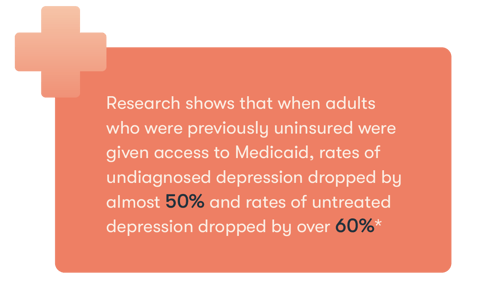

Although this is an improvement over their 2009 recommendations, this continues to present barriers to people who lack adequate health insurance. Indeed, research shows that when adults who were previously uninsured were given access to Medicaid, rates of undiagnosed depression dropped by almost 50% and rates of untreated depression dropped by over 60% [16]. Given that depressive disorders are a leading cause of disability [17] and the increased burden of undiagnosed depression, increasing access to screening tools and mental health support should be a priority.

Although this is an improvement over their 2009 recommendations, this continues to present barriers to people who lack adequate health insurance. Indeed, research shows that when adults who were previously uninsured were given access to Medicaid, rates of undiagnosed depression dropped by almost 50% and rates of untreated depression dropped by over 60% [16]. Given that depressive disorders are a leading cause of disability [17] and the increased burden of undiagnosed depression, increasing access to screening tools and mental health support should be a priority.

Many researchers call for equipping more people to conduct screenings, like pharmacists [18], while others recognize the need for options that offer people convenient, engaging and accessible ways to perform mental health checks for themselves.

Moreover, given the high number of individuals with unrecognized depression, methods of estimating depression that feel less clinical may be important to increasing uptake of screening tools.

Bottom line: I normalized living with depression for far longer than was necessary. Too many people suffer from depressive symptoms without realizing it, and the more time that passes that they go untreated, the greater the costs on our healthcare system and the greater the toll on the individuals and their loved ones. We must continue to expand access to destigmatized depression screening tools to reach more people, sooner.

References

[1] Epstein, R. M., Duberstein, P. R., Feldman, M. D., Rochlen, A. B., Bell, R. A., Kravitz, R. L., ... & Paterniti, D. A. (2010). “I didn’t know what was wrong:” how people with undiagnosed depression recognize, name and explain their distress. Journal of general internal medicine, 25(9), 954-961.

[2] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2019. HHS Publication No. PEP19-5068, NSDUH Series H-54. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

[3] Thornicroft, G., Chatterji, S., Evans-Lacko, S., Gruber, M., Sampson, N., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., ... & Kessler, R. C. (2017). Undertreatment of people with major depressive disorder in 21 countries. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 210(2), 119-124.

[4] Williams, S. Z., Chung, G. S., & Muennig, P. A. (2017). Undiagnosed depression: A community diagnosis. SSM-population health, 3, 633-638.

[5] Lotfaliany, M., Bowe, S. J., Kowal, P., Orellana, L., Berk, M., & Mohebbi, M. (2018). Depression and chronic diseases: Co-occurrence and communality of risk factors. Journal of affective disorders, 241, 461-468.

[6] Frey, J., Osteen, P., Name, B., & Mosby, A. (2020, January). More than just depression: The need to screen for anger as suicide risk among working-aged men. Paper presented at the Society for Social Work and Research 24th Annual Conference, Washington, DC.

[7] Magovcevic, M., & Addis, M. E. (2008). The Masculine Depression Scale: development and psychometric evaluation. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 9(3), 117.

[8] Cavanagh, A., Wilson, C. J., Kavanagh, D. J., & Caputi, P. (2017). Differences in the expression of symptoms in men versus women with depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Harvard review of psychiatry, 25(1), 29-38.

[9] Rice, S. M., Kealy, D., Oliffe, J. L., & Ogrodniczuk, J. S. (2019). Externalizing depression symptoms among Canadian males with recent suicidal ideation: A focus on young men. Early intervention in psychiatry, 13(2), 308-313.

[10] Rice, S. M., Fallon, B. J., Aucote, H. M., & Möller-Leimkühler, A. M. (2013). Development and preliminary validation of the male depression risk scale: Furthering the assessment of depression in men. Journal of affective disorders, 151(3), 950-958.

[11] Chang, M. X. L., Jetten, J., Cruwys, T., & Haslam, C. (2017). Cultural identity and the expression of depression: A social identity perspective. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 27(1), 16-34.

[12] Dreher, A., Hahn, E., Diefenbacher, A., Nguyen, M. H., Böge, K., Burian, H., ... & Ta, T. M. T. (2017). Cultural differences in symptom representation for depression and somatization measured by the PHQ between Vietnamese and German psychiatric outpatients. Journal of psychosomatic research, 102, 71-77.

[13] Aragonès, E., Labad, A., Piñol, J. L., Lucena, C., & Alonso, Y. (2005). Somatized depression in primary care attenders. Journal of psychosomatic research, 58(2), 145-151.

[14] Melek, S., & Halford, M. (2012). Measuring the cost of undiagnosed depression. Contingencies. https://www.milliman.com/-/media/milliman/importedfiles/uploadedfiles/insight/research/health-rr/pdfs/cost-of-undiagnosed-depression.ashx

[15] Siu, A. L., Bibbins-Domingo, K., Grossman, D. C., Baumann, L. C., Davidson, K. W., Ebell, M., ... & US Preventive Services Task Force. (2016). Screening for depression in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Jama, 315(4), 380-387.

[16] Baicker, K., Allen, H. L., Wright, B. J., Taubman, S. L., & Finkelstein, A. N. (2018). The effect of Medicaid on management of depression: evidence from the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment. The Milbank Quarterly, 96(1), 29-56.

[17] James, S. L., Abate, D., Abate, K. H., Abay, S. M., Abbafati, C., Abbasi, N., ... & Briggs, A. M. (2018). Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet, 392(10159), 1789-1858.

[18] Miller, P., Newby, D., Walkom, E., Schneider, J., & Li, S. C. (2020). Depression screening in adults by pharmacists in the community: a systematic review. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice, 28(5), 428-440.

About the Author

Eliane Boucher, PhD, Senior Director of Research Strategy has a PhD in Social/Personality Psychology and spent more than a decade in academic research before joining Twill. She helps to oversee Twill's program of research, including analyzing platform data, prospective studies on the impact of Twill products in various populations, patient-centered research, and other foundational research.

Read more articles by Eliane Boucher, PhD, Senior Director of Research Strategy.