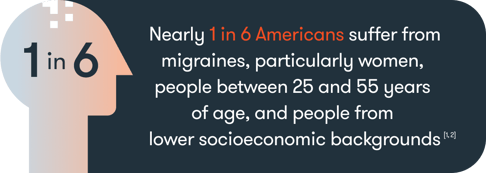

More than 45 million Americans aged 18 years or older report having a migraine or severe headache in the last 3 months, according to the CDC.

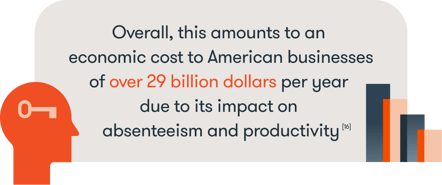

Migraines cost the United States $36 billion annually; they are the 5th leading cause of ER visits and account for 22% of missed days of work.

In an observational study with 5,000 migraine sufferers, Twill showed positive impact on mental wellbeing, quality of life, migraine pain, and frequency. Continue reading or download our white paper to learn about which populations are particularly impacted by migraines, a detailed breakdown of healthcare costs, and what our research reveals about how digital therapeutics can help.

Who Gets Migraines?

Migraines affect 1 billion people, making it the 3rd most prevalent illness in the world.

Most people experience more episodic migraines, but more than 4 million Americans have chronic migraines, which means they have more than 15 per month [3].

What’s worse is that 3-5% of episodic migraine cases became chronic [4, 5] and some reports suggest this number doubled during COVID-19 [6].

The Cost of Migraines

Migraines typically impact people during their most productive working years, which makes the disability burden especially high [7].

Globally, migraines represent one of the leading causes of disability [8]. In total migraines account for 9.5% of all years of healthy life lost to a disability among people ages 15 to 49 [9].

In particular, people who suffer from chronic migraines have 3.63 times more disability days than people with episodic migraines [10], and people with chronic migraine make up 40-45% of the people visiting headache clinics [11, 12].

Medical costs among migraine sufferers are, on average, 1.7x higher than in the general population [13]; inpatient costs alone may be as high as 1.2 billion per year nationwide [14].

The cost associated with chronic migraine is even higher; approximately 3x the cost associated with an episodic migraine[15], and episodic migraines that transform into chronic migraine are associated with 4.4x higher costs than those that remain episodic [4].

On average, migraines are associated with 4.4 missed workdays per year plus an average of 11.4 days per year with reduced productivity [17]. That’s the equivalent of about 157 million total lost workdays in the U.S. per year due to migraines [18].

Migraine Patients Need New Options

Despite these high costs, funding for migraine research is comparatively low [13] and migraines remain an under-diagnosed and under-treated condition[19]. What’s more, many migraine patients report being dissatisfied with their treatment options and often stop whatever treatment they started to try and address the problem[20].

Exploring new options for migraine patients and new delivery modalities is imperative.

Stress seems to be an important part of the migraine cycle; not only is it the most commonly reported trigger for migraines [21], but experiencing a migraine also heightens one’s level of stress [22]. People who suffer from migraine sufferers are also more likely to suffer from anxiety and depression [22].

Most current treatment options for migraine sufferers are focused on addressing the physical components of a migraine. An alternative approach to treating migraines is to help people reduce their stress, depression, and anxiety. If it were possible to reduce stress, depression, and anxiety for a migraine sufferer, then the potential is there to reduce the primary triggers for migraines and improve a person’s overall quality of life at the same time.

However, so far, these biobehavioral treatments have been limited to face-to-face settings, which introduces several roadblocks to receiving care.

At Twill, our hypothesis was that our digital-first approach to offering biobehavioral treatments for migraine has the potential to provide a scalable and cost-effective way to help migraine sufferers, without them ever needing to leave their home or office.

Twill’s Digital-First Approach to Helping Migraine Patients

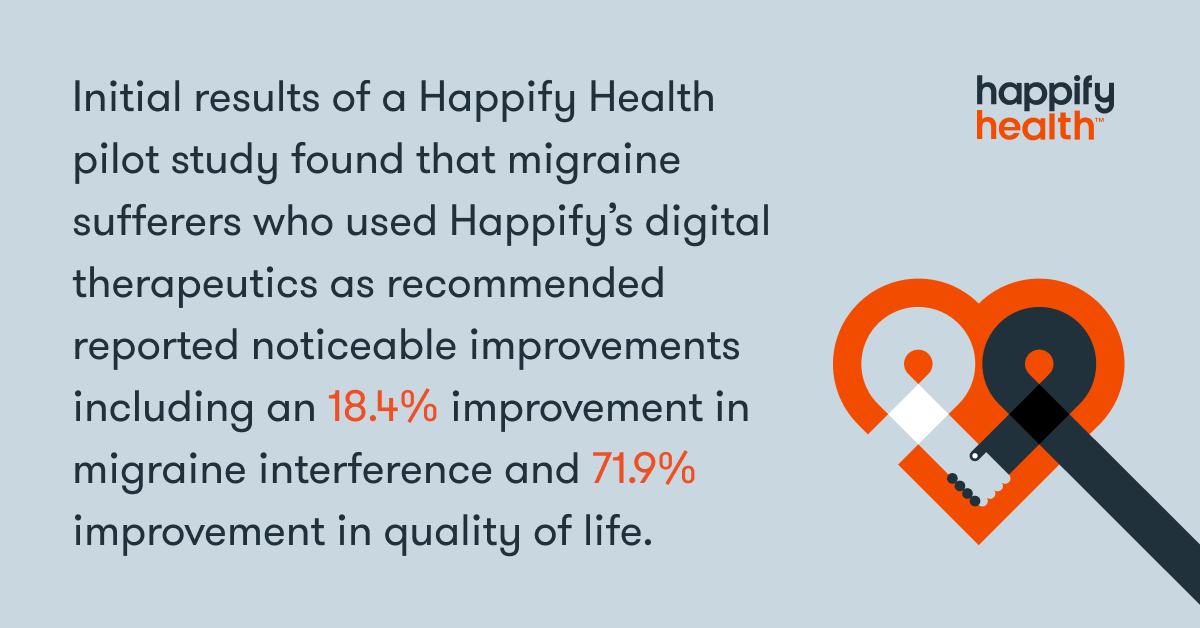

Beginning in 2020, Twill launched a pilot study to measure the effects of our digital therapeutics platform on people with self-reported migraines.

Initial results from the pilot study found that 70% of the users we engaged had anxiety and 88% had well-being scores below the 50th percentile for the general population. People with chronic migraines were even worse off; compared

to users with less than 4 migraines per month, anxiety was 15.15% higher and subjective well-being was 16.16% lower among users with 15 or more migraines per month.

The Good News

Following the pilot study, our data illustrated that users suffering from migraines showed significant improvements in both well-being and anxiety after using Twill, especially when they completed our recommended 16 activities.

Twill's data also showed that when users successfully reduced their anxiety or stress levels, they also reported fewer migraines over time. These preliminary findings provide some promising insights into how digital therapeutics may help improve mental health and migraine-related outcomes.

Identifying new ways to address the mental and physical toll of migraines is an important step in increasing access to care and reducing the cost burden on our healthcare system.

References

- Burch, R., Rizzoli, P., & Loder, E. (2018). The Prevalence and Impact of Migraine and Severe Headache in the United States: Figures and Trends From Government Health Studies. Headache, 58(4), 496–505. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13281

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, March 26). QuickStats: Percentage of Adults Who Had a Severe Headache or Migraine in the Past 3 Months, by Sex and Age Group - National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2018. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6912a8.htm.

- Lipton, R. B., & Bigal, M. E. (2005). Migraine: epidemiology, impact, and risk factors for progression. Headache, 45 Suppl 1, S3–S13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.4501001.x

- Munakata, J., Hazard, E., Serrano, D., Klingman, D., Rupnow, M. F., Tierce, J., Reed, M., & Lipton, R. B. (2009). Economic burden of transformed migraine: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study. Headache, 49(4), 498–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01369.x

- May, A., & Schulte, L. H. (2016). Chronic migraine: risk factors, mechanisms and treatment. Nature reviews. Neurology, 12(8), 455–464. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2016.93

- Al-Hashel, J. Y., & Ismail, I. I. (2020). Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on patients with migraine: a web-based survey study. The journal of headache and pain, 21(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-020-01183-6

- Steiner, T. J., Stovner, L. J., Jensen, R., Uluduz, D., Katsarava, Z., & Lifting The Burden: the Global Campaign against Headache (2020). Migraine remains second among the world's causes of disability, and first among young women: findings from GBD2019. The journal of headache and pain, 21(1), 137. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-020-01208-0

- Stovner, L. j., Hagen, K., Jensen, R., Katsarava, Z., Lipton, R., Scher, A., Steiner, T., & Zwart, J. A. (2007). The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia : an international journal of headache, 27(3), 193–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01288.x

- GBD 2016 Headache Collaborators (2018). Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet. Neurology, 17(11), 954–976. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30322-3

- Adams, A. M., Serrano, D., Buse, D. C., Reed, M. L., Marske, V., Fanning, K. M., & Lipton, R. B. (2015). The impact of chronic migraine: The Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study methods and baseline results. Cephalalgia : an international journal of headache, 35(7), 563–578. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102414552532

- Pascual, J., Colás, R., & Castillo, J. (2001). Epidemiology of chronic daily headache. Current pain and headache reports, 5(6), 529–536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-001-0070-6

- Diener, H. C., Solbach, K., Holle, D., & Gaul, C. (2015). Integrated care for chronic migraine patients: epidemiology, burden, diagnosis and treatment options. Clinical medicine (London, England), 15(4), 344–350. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.15-4-344

- Polson, M., Williams, T. D., Speicher, L. C., Mwamburi, M., Staats, P. S., & Tenaglia, A. T. (2020). Concomitant medical conditions and total cost of care in patients with migraine: a real-world claims analysis. The American journal of managed care, 26(1 Suppl), S3–S7. https://doi.org/10.37765/ajmc.2020.42543

- Law, H. Z., Chung, M. H., Nissan, G., Janis, J. E., & Amirlak, B. (2020). Hospital Burden of Migraine in United States Adults: A 15-year National Inpatient Sample Analysis. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Global open, 8(4), e2790. https://doi.org/10.1097/GOX.0000000000002790

- Messali, A., Sanderson, J. C., Blumenfeld, A. M., Goadsby, P. J., Buse, D. C., Varon, S. F., Stokes, M., & Lipton, R. B. (2016). Direct and Indirect Costs of Chronic and Episodic Migraine in the United States: A Web-Based Survey. Headache, 56(2), 306–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12755

- Robbins, M. (2015, January 1). Migraine – Where We Are and Where We Are Going: AMF. American Migraine Foundation. https://americanmigrainefoundation.org/resource-library/migraine-where-we-are-and-where-we-are-going/.

- Leonardi, M., & Raggi, A. (2019). A narrative review on the burden of migraine: when the burden is the impact on people's life. The journal of headache and pain, 20(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-019-0993-0

- Migraine Facts. Migraine Research Foundation. (2021, January 15). https://migraineresearchfoundation.org/about-migraine/migraine-facts/.

- Bartleson J. D. (1999). Treatment of migraine headaches. Mayo Clinic proceedings, 74(7), 702–708. https://doi.org/10.4065/74.7.702

- Aukerman, G., Knutson, D., Miser, W. F., & Department of Family Medicine, Ohio State University College of Medicine and Public Health, Columbus, Ohio (2002). Management of the acute migraine headache. American family physician, 66(11), 2123–2130.

- Andress-Rothrock, D., King, W., & Rothrock, J. (2010). An analysis of migraine triggers in a clinic-based population. Headache, 50(8), 1366–1370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.2010.01753.x

- Malone, C. D., Bhowmick, A., & Wachholtz, A. B. (2015). Migraine: treatments, comorbidities, and quality of life, in the USA. Journal of pain research, 8, 537–547. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S88207

- Silberstein S. D. (2000). Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology, 55(6), 754–762. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.55.6.754

About the Author

Eliane Boucher, PhD, Senior Director of Research Strategy has a PhD in Social/Personality Psychology and spent more than a decade in academic research before joining Twill. She helps to oversee Twill's program of research, including analyzing platform data, prospective studies on the impact of Twill products in various populations, patient-centered research, and other foundational research.

Read more articles by Eliane Boucher, PhD, Senior Director of Research Strategy.